The seven principles of scientific writing

August 08, 2014“The enthalpy of hydrogen bond formation between the nucleoside bases 2’deoxyguanosine (dG) and 2’deoxycytidine (dC) has been determined by direct measurement. dG and dC were derivatized at the 5’ and 3’ hydroxyls with triisopropylsilyl groups to obtain solubility of the nucleosides in non-aqueous solvents and to prevent the ribose hydroxyls from forming hydrogen bonds. From isoperibolic titration measurements, the enthalpy of dC:dG base pair formation is -6.65±0.32 kcal/mol.”

Do you have any idea what’s going on in the paragraph above? Unless you’re a chemist, there are probably a lot of unfamiliar words—but that’s not the only problem.

The Science of Scientific Writing is one of the best articles I’ve read about the trouble with scientific writing and how to fix it. It was first published in 1990, but things haven’t changed. From the introduction:

Science is often hard to read. Most people assume that its difficulties are born out of necessity, out of the extreme complexity of scientific concepts, data and analysis. We argue here that complexity of thought need not lead to impenetrability of expression; we demonstrate a number of rhetorical principles that can produce clarity in communication without oversimplifying scientific issues. The results are substantive, not merely cosmetic: Improving the quality of writing actually improves the quality of thought.

These are pretty radical ideas. The topic of good writing often provokes only apathy in scientists—“This is complicated stuff, you can’t expect it to be easy to read”—“I’ve never been an English person, but you know what I meant to say”—“Well, the science is good, that’s what’s important.” This article argues that

- Yes, science is complicated, but it doesn’t have to be hard to read about, even in technical publications.

- Clear writing is not some magical art form that technical people can’t grasp.

- Writing more clearly can actually make you a better scientist.

Authors George Gopen and Judith Swan go on to explain that readers expect to see certain information in certain locations in a sentence or paragraph. Writing is easy to follow when these expectations are met, and more difficult when these expectations are frustrated. If the writer is familiar with the reader’s expectations, it’s possible to construct friendly sentences about difficult concepts.

The article gives seven specific guidelines for fixing bad sentences, with examples from real publications. It focuses on making prose more readable by altering the sentence structure, not by dumbing down the science. I recommend it for anyone who writes journal papers, conference submissions, grant proposals, lab reports, a thesis, or any other kind of technical writing.

Actually, it’s also good for anyone who has to read this stuff. Remember when you first learned to read, and your teacher told you to “use context clues” to figure out the meaning of a word you didn’t know? Some sentences are so twisted and backwards that those context clues aren’t even there. It’s no wonder you feel like a first grader again—it’s not just that the subject is complicated or unfamiliar, but the language isn’t leading you to the meaning the way it should.

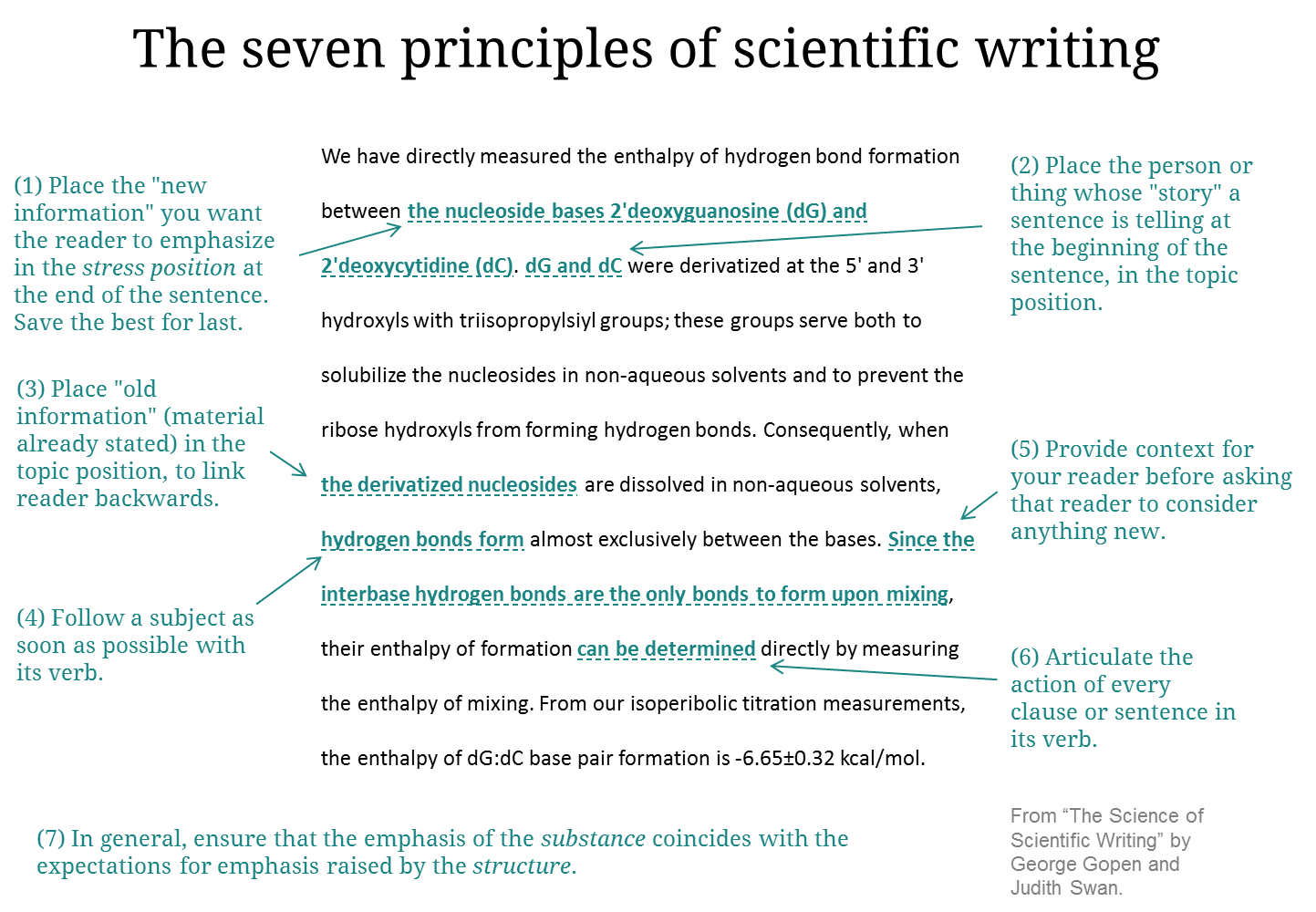

To show how it works, I’ve taken an example from the article (the paragraph at the top of this post) and marked up Gopen and Swan’s revised version. I tried to find an example of every principle, but the full article has many more examples that illustrate each of them more clearly.

Much easier to follow, right?

If research papers were easier to read, I bet scientists (and non-scientists!) would read a lot more of them.

Obviously, this is not necessarily writing advice for novelists—sometimes there are artistic reasons to surprise the reader. And there’s more to good writing than just making the reader feel comfortable. But it’s a good place to start, especially for technical types who want a technical answer about why a sentence is confusing.

Finally, a word about following the rules:

None of these reader-expectation principles should be considered “rules.” Slavish adherence to them will succeed no better than has slavish adherence to avoiding split infinitives or to using the active voice instead of the passive. There can be no fixed algorithm for good writing, for two reasons. First, too many reader expectations are functioning at any given moment for structural decisions to remain clear and easily activated. Second, any reader expectation can be violated to good effect. Our best stylists turn out to be our most skillful violators; but in order to carry this off, they must fulfill expectations most of the time, causing the violations to be perceived as exceptional moments, worthy of note.

But they are pretty good rules.