On paper

July 23, 2014This is a re-post of something I wrote in spring 2011. It has been slightly edited (only where I couldn't resist).

I keep a slightly crumpled, five-foot strip chart rolled up in a desk drawer. It was briefly featured on the refrigerator, but it was constantly falling down or being swarmed by Chinese take-out menus. It also lived above a window in my bedroom for a while, but the tape didn’t stick to the stucco very well. Eventually it came down for good.

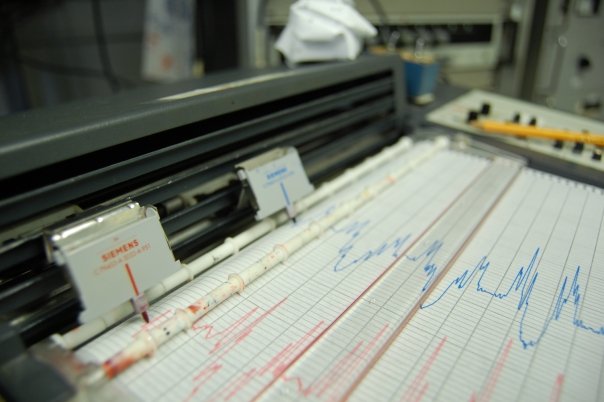

The strip chart shows the center of the Milky Way in radio waves. I recorded it while spending a week at a National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) in the mountains of West Virginia a few years ago. Other students and I had access to an educational 40-foot radio dish hooked up to a bank of ancient electronics, including the strip chart recorder. The charts look a lot like seismograph recordings of earthquakes, but the sizes of the little peaks and valleys correspond to the strength of radio signals from space, not jitters in the ground. (By the way—a lot of those radio waves coming from the center of the Milky Way are produced by a supermassive black hole.)

Using that equipment was a real pain. Switches had to be flipped in a certain inexplicable order or nothing worked, and the manual wasn't much help. The analog pointing system wouldn’t hold a calibration and had to be re-adjusted each night to make sure it was still looking at the bit of sky we thought it was. The radio dish only moved on a large arc from north to south, which meant aiming at the right slice of sky and waiting for the earth to turn, bringing any objects we wanted to observe into view. This could happen at 3 AM.

The strange thing about the National Radio Astronomy Observatory is that it’s full of high-tech telescopes—much more modern than the clunker we got to use as students—but these telescopes don’t function properly in the presence of a lot of other technology. Cell phones and even the spark plugs in gasoline-powered vehicles emit enough radio waves to fuzz up sensitive telescopes. A sign at the entrance to the observatory warns with ominously haphazard capitalization:

You are Entering the Radio Astronomy Instrument Zone. Diesel Vehicles Only. No Portable Electronics except for Authorized Purposes. Do Not Install or Leave Unattended any equipment that does not comply with ITU-H RA.759.

A fleet of rusty diesel Rabbits and taxicabs ferry astronomers with equipment too heavy to move by bicycle out to the telescopes. No wireless internet is allowed in the dormitory a few hundred feet from the observatory gates.

It's all a real pain.

It’s also beautiful to ride an old, squeaky bicycle down a black gravel road to a radio telescope in the middle of the night. I think all astronomers must know something about this, although many of them probably wouldn’t get so sentimental about it. It’s beautiful to watch the pink felt-tip pen of a chart recorder scratch out of the center of the galaxy—up and down, and up, and down—with reassuring electronic whirs.

Having this experience also meant that when I got the chance to hear Jocelyn Bell Burnell tell the story of how she discovered pulsars after noticing an unusual signal on a strip chart, I knew exactly what she was talking about. She analyzed miles of strip charts by hand as a graduate student. She kept them organized in shoeboxes in the lab.

Of course, all the other radio telescopes at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory record data with computers. (In fact, even the 40-foot telescope can now do this too.) It would be impossible to handle the data output of modern telescopes without them. Astronomers use computers to analyze the data, create graphs and images, and write their scientific papers.

The lab that I work for at UNC even uses an internet-based log system instead of paper lab notebooks. It’s useful to get updates on an experiment by email and to be able to search our records for particular terms, but sometimes I still want to make a quick sketch or scribble in a margin.

I’m all for the romance of the strip chart recorder, but I find it tedious to actually hand-plot or analyze anything in the lab. I jot down ideas for poems on paper sometimes, but I never draft a poem or an essay without my laptop. When editing my own work or an article for Carolina Scientific, I scribble all over the page, drawing arrows, question marks, circling words, underlining. On paper I see typos and awkward phrases I miss on the screen. I’ve tried using electronic copies of textbooks, but after five minutes of reading on my laptop I’ll use any excuse to get up and do something else. I long for a keyboard, however, whenever I have to write a long essay by hand for a midterm. I hate reading on a computer, but I can’t write without one.

I find composing on paper difficult, but does it really affect the quality of my writing? Could I even be a better writer on paper? Or a better scientist?

If you too want to spend a week doing radio astronomy at NRAO, apply for the 2011 Educational Research in Radio Astronomy program! ERIRA is run every summer by Dr. Dan Reichart and other educators from UNC-Chapel Hill and universities around the country. 2011 applications are due Monday, April 11. The program will take place from Saturday, June 18 to Friday, June 24 (Saturday and Friday are travel days). Participants are selected "on the basis of enthusiasm first, and background in astronomy and science second."